A New Claim to have deciphered TheVoynich Manuscript has been made by British Scholar Gerard Cheshire but it is doubtful

In a recently published article, a British Academic stuns claiming to have solved the centuries-old puzzle.

The latest claim to have successfully deciphered Manuscript MS408 a.k.a. the Voynich Manuscript has been made last month by Gerard Cheshire, an academic with the University of Bristol (and that claim has already been revised for inaccuracies). The manuscript acquired its catalogue code MS408 when it was acquired by Yale University and stored at its Beinecke Library.

It got its name from a Polish antiquarian book dealer, named Wilfred Voynich who purchased it in 1912. The strange, cryptic, written in an unknown language manuscript began soon to attract the attention of many researchers and amateur sleuths as well. Numerous claims in the course of the years were made to solve its riddle but no one really seems to have succeeded as of yet.

Cheshire revised the linguistics of the Voynich and presented new ideas

Cheshire analyzed the Voynich and found that it is unusual in a number of respects: the manuscript was written in an extinct, unrecorded language. Some of the letters include symbols to indicate punctuation with some of the symbols indicating phonetic accents as well as using an unknown writing system with no punctuation marks. It also mixes unfamiliar symbols along with more familiar symbols. According to Cheshire, other particularities includes that all the text is in lower case; it does not contain double consonants. but it includes diphthong ( like ‘oil’ ), triphthongs ( like ‘fire’ ), quadriphthongs ( like ‘miaou’ ) and even quintiphthongs ( like ‘dumbstruck’ ). He adds that some of the manuscript text uses some words and abbreviations in Latin. Cheshire believes that he rapidly solved the mystery while no one else has succeeded in one century. So it should come to no surprise that other scholars are not impressed with his bold claim.

Earlier studies have revealed that the manuscript is a sort of almanac filled with information on herbal remedies, therapeutic bathing and astrological readings that encompasses all kind of subjects, such as the female mind, the body, natural reproduction, parenting and others “in accordance,” as Cheshire puts it, “with the Catholic and Roman pagan religious beliefs of Mediterranean Europeans during the late Medieval period”.

In particular, Cheshire insists, the manuscript was probably compiled by a Dominican nun as a source of reference for the female royal court to which her monastery was affiliated. That is not an uncommon occurrence in the history of medieval science. However, the field of women’s’ studies was not a favorite of nuns, except maybe in the secrecy of their alcoves. It is hard to imagine they would keep such materials under the supervision of the Church.

Critics such as J.K. Petersen object to Cheshire’s claims

Cheshire asserts that the manuscript uses a language that arose from a blend of spoken Latin, or Vulgar Latin, and other languages across the Mediterranean during the early Medieval period following the collapse of the Roman Empire and subsequently evolved into the many Romance languages, including Italian. For that reason, says Cheshire, it is known as proto-Romance or prototype-Romance. But what exactly do the terms “proto-Romance” and “proto-Italic” mean? Critics, such as J.K. Petersen, immediately objected that there is no such a thing as one ‘Proto-Romance’ language and that his claim is completely unfounded and contradicts what we know of ancient languages. Cheshire thinks that Voynichese is an extinct proto-Romance language redacted in an undocumented proto-Italian script which would be something that existed about 1000 years before the creation of the manuscript. According to radiocarbon dating, the manuscript was made in the early 15th century and so such a difference is suspicious. Cheshire doesn’t provide a credible explanation of how the information could have been transmitted a thousand years into the future if it was an extinct proto-Romance language. It is possible there is a Romance language buried somewhere in the text but Cheshire is not suggesting this. Only the location where the manuscript was found in Italy would support this thesis.

MS408 alphabet is just as our modern Italic alphabet, but it contains a number of unfamiliar characters, that seem to be of a foreign origin or even completely unknown and without a reference in other languages. Some letters are also missing for various reasons, maybe because they are silent or they are unpronounced in the manuscript peculiar writing.

In addition, there are various combined letter symbols — diphthongs, triphthongs mentioned earlier — used to represent specific phonetic sounds or to abbreviate frequently used phonetic components.

Furthermore, examples of Latin stock-phrases are found by the sole abbreviation of initial letters, because “they were familiar to the contemporaneous reader”, according to Cheshire. Standard practice was to write with single consonants during the Medieval period as a vestige of Vulgar Latin. Double consonants returned with the Renaissance when more sophisticated linguistic nuances became desirable.

Cheshire posits that the writing system of the manuscript can be apprehended once the grammatical rules are understood. Like all natural writing systems, it evolved by cultural selection and was, therefore, designed by the process of social use to be linguistically economical and efficient. Despite this, says Cheshire, it had a number of flaws that prevented it from evolving into a popular form.

In addition to the alphabet symbols, a number of combined symbols is shown and explained. The manuscript uses only lowercase letters and there are no punctuation marks either, so punctuation is indicated by the use of symbol variants and spacing.

Some examples of Cheshire’s finds are worth considering

To his credit, Cheshire’s study is very well documented including no less than 60 figures to illustrate his theory.

The first half of the documentation refers to grammar, linguistics, writing.

Cheshire takes a glyph-shape that is known to paleographers as the Latin “-cis” abbreviation (the letter c plus a loop that usually represents “is” and its homonyms). This shape is both a ligature and an abbreviation in languages that use Latin scribal conventions. It has not yet been determined what it means in the Voynich, but its positional characteristics are similar to texts that use the Latin alphabet. Voynich researchers know this shape as EVA-g.

As we can see above, Cheshire transliterates it as a “ta” diphthong. Cheshire did not address the basis statistics of Voynich text and the fact that this glyph occurs primarily at the ends of words and sometimes the end of lines. Thus transliterating EVA-g as “ta” is highly questionable. Another of Petersen’s criticism is that Cheshire doesn’t appear to have noticed this unusual distribution (at least he doesn’t comment on this important dynamic in his paper) and translates the leading glyph in the same ways as the others. In his system, a very large number of paragraphs begin inexplicably with the letter “P”.

Petersen asserts that, if Voynichese were a proto-Romance language — some form of classical Vulgar Latin — and EVA-x were transliterated to U/V and also F/PH, as per Cheshire’s system, one would expect to see this character more than 40,000 times in 200+ pages. Instead, this character occurs less than 50 times. That, alone, says Petersen, should create doubt in people’s minds about Cheshire’s “solution”.

Petersen finally concludes that as Cheshire’s reading of the letters is wrong, then his transliteration is going to be wrong as well.

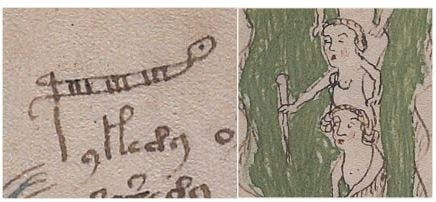

Some of his translations cannot be verified, says Petersen. For example, he used a drawing from folio 75 to demonstrate a single transliterated word, “palina”, on folio 79. Other than what he contends, there is no apparent relationship between them. According to Petersen it would be even more unlikely that an independent party determine if the translation is correct. Below to the left can the symbol be seen.

The second half of Cheshire’s examples relates to the images and texts examples.

Critics deconstruct some of Cheshire’s conclusions as too shaky

Cheshire claims that the figure below, figure 31

shows an illustration of a bearded monk in his washtub, from the monastery where the manuscript was created. Cheshire believes the words read: opat a sa (it is abbot). By the way he is one of very few male faces seen in the manuscript. The word opát survives to mean abbot in Polish, Czech and Slovak, demonstrating that proto-Romance reached as far as Eastern Europe. In Western Europe other variants survive: abat (Catalan), abad (Spanish), abbé (French), whilst the Latin is ‘abbas’. This also demonstrates the phonetic overlap between the sounds ‘p’ and ‘b’ in the manuscript alphabet.

But Petersen calls it a “tenuous assertion”. “On folio 70”, says Petersen, “Cheshire uses a circular argument to explain the transliteration of “opat” (which he says means “abbot”). Cheshire says the use of “opat” indicates “that proto-Romance reached as far as Eastern Europe” because “opat survives to mean ‘abbot’ in Polish, Czech and Slovak”. Petersen doesn’t need a dubious transliteration to tell us that proto-Romance languages reached Eastern Europe.

“The existence of Romania demonstrates this rather well-it borders the Ukraine, and used to encompass parts of Bohemia. Bohemia included Hungary, the Czech Republic, and parts of Eastern Germany, so transmission of Vulgar Latin to Polish through Czech was a natural process.”

Cheshire mentions the Gemini zodiac figures (the male/female pair), and states: “Both figures are wearing typical aristocratic attire from the mid 15th Century Mediterranean.”

It takes research to determine the location and time period for specific clothing styles-it’s not something people just automatically know. Since Cheshire didn’t credit a source for this reference, one can assume it’s possible he got the information somewhere else.

As for the flora and the fauna, Petersen says he is not going to deal with Cheshire’s fish identification, which he assures us is just as dubious as the Janick and Tucker alligator gar.

Petersen continues, “there are fish that are more similar to the Voynich Pisces that Cheshire’s sea bass, and pointing out that the fact that sea bass has “scales” is like pointing out that a bird has wings”.

Petersen concludes that he was hopeful that Cheshire’s latest paper would be an improvement over his previous efforts, but he was disappointed.

The conclusion? Maybe Cheshire’s study deserves attention but it is not a final answer to the Voynich’s decryption

Finally, Cheshire’s last two samples refer to a Second Manuscript, by Loise De Rosa, called “De Regno di Napoli”, which may be referring to the Voynich. Cheshire says that the lexicon of De Rosa’s text is “scattered amongst Latin and the Romance languages, just like that of the Voynich.” “De Rosa’s text provides documentation of a writing system and a language similar to those of the Voynich, demonstrating that both evolved from the same naïve linguistic rootstock.”

What Cheshire means is that the Voynich and the De Regno came from Vulgar Latin, however in different ways. He goes as far As saying that De Rosa may have met the author of the Voynich when De Rosa took refuge in Ischia for political reasons.

Petersen points out that Cheshire’s descriptions of individual glyphs, and his interpretations of the annotations shown above, suggest that he is not familiar with medieval scripts.

A Turkish claim seems worth considering and has been praised by some scholars

As another of Cheshire’s critics, Dr. Fagin Davis, asserted, “The claim has to be based on sound principles, must be reproducible by other investigators, and follow conformance to linguistic and codicological facts”. The text must also make sense and there must be a correspondence between the text and the illustrations. According to her, only the research made by a Turkish team, whose results were published a year ago, seems to fit several of these requirements.

Ahmet Ardiç, a Turkish electrical engineer working with his sons, claimed in 2018 that the Voynich text is written in a phonetic form of Old Turkish. He has so far translated 300 words and has earned the respect of Dr. Fagin Davis, who said that it is “one of the few solutions I’ve seen that is consistent, repeatable and results in sensical text.”

Without going into the technical aspects of Ardiç’s research, only from reading the manuscript and looking at the strange illustrations, I believe, like many do, the manuscript is of alchemical origin. For example, the mysterious illustrations in which naked women seated in ‘tubes’ seem to place their hands into the openings of these ‘tubes’ make me think of alembics. The strangeness comes from the fact that the alembics must either be of a giant size, or the nymphs emerging from them must be very small. Or they are metaphors of something else, possibly meaning the feminine part of some ‘alchemical’ process. The alchemist Mary the Jewess, known for her outstanding work, might find some resonance here.

This is not the last claim but I will offer some opinion on the subject

I personally like the interpretation held by Ardiç and his sons. We know that the Orient played a great role in patronizing alchemy, and the Arabs in particular played an important part. The Turkish being in close contact, it would now throw some light on the possibility that the manuscript could have been redacted in the Middle East and translated in proto-Turkish. Then it would have in some ways (fortuitous or else) landed in Ischia and have finished in the hands of the Aragonese family. The role of the Turkish people in science is not new. A very famous example is the 1530 world map that belonged to Turkish admiral Piri Reiss. It is possible in my view that the Turks would have obtained a copy of the original manuscript from the Arab world, copied it in phonetic form as they translated it, and thus created the Voynich manuscript. The manuscript was later acquired by the Aragonese and finally ended at the nunnery in the castle in Ischia.

This is one of many possible interpretations and only more research, or the next claim of the Voynich’s transliteration, will confirm what really the Voynich meant. Or we may also never know the solution of one of the unresolved ancient mysteries.

References:

1 — The Language and Writing System of MS408 (Voynich) Explained: by Gerard Cheshire

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02639904.2019.1599566

2 — Cheshire Reprised: by J.K. Petersen

https://voynichportal.com/2019/05/16/cheshire-reprised/

3- Dr Fagin Davis at Medieval Academy